This write up covers my experience with the Skill Check Labs CTF, an interactive collection of challenges designed to put fundamental web reconnaissance skills to the test. Each flag in this lab had me investigating real-world security scenarios like web server banners, configuration files lurking in the open, and the power of directory and file enumeration.

I approached each task with classic tools like curl, WhatWeb, DirB, and HTTrack, recording my process and sharing what worked, what didn’t, and how each hint led to the next flag. If you’re new to CTFs or just want to see how standard web pentesting tools solve practical problems, this blog post covers the step-by-step logic, methods, and aha moments throughout the five-flag journey.

Flag 1: This tells search engines what to and what not to avoid.

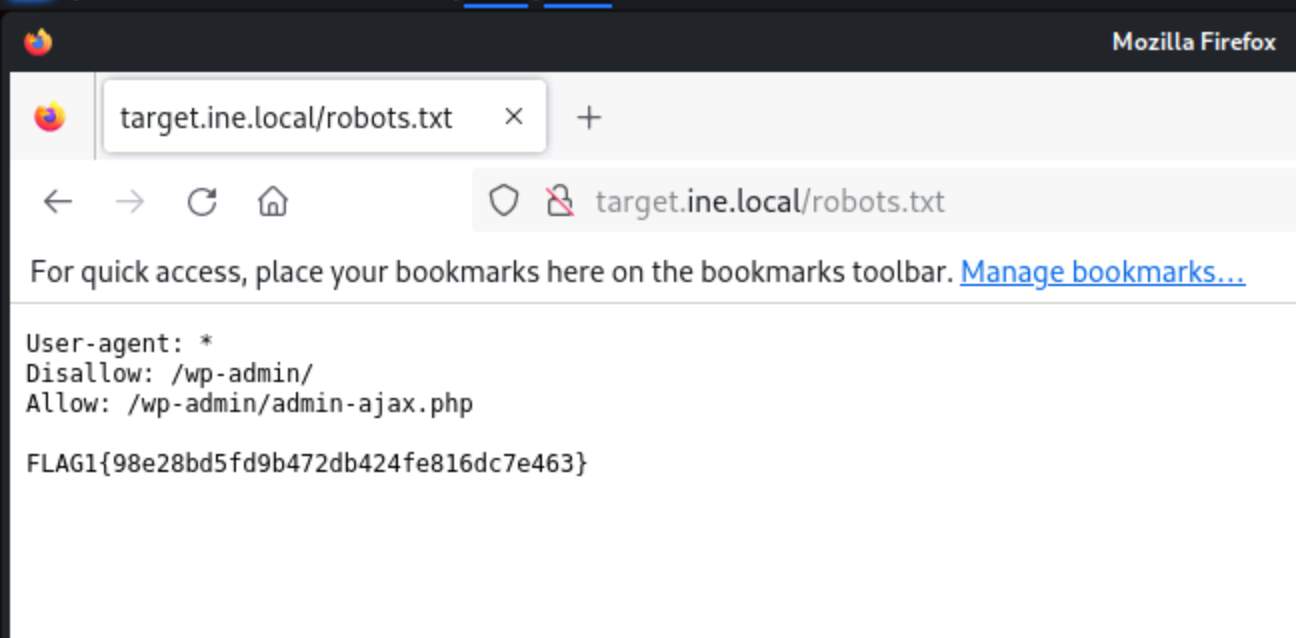

Starting off the CTF, the first flag asked about something “that tells search engines what to and what not to avoid.” I instantly thought of the robots.txt file basically the rulebook for search engine bots. It lives at the root of pretty much every website and spells out which folders and files should be ignored by automated crawlers.

So, my first move was to check out the robots.txt file. I could’ve opened it in Firefox, but I went with the terminal, running:curl http://target.ine.local/robots.txt

This is a super common place for CTF creators to stash an early flag, so I scanned through the file’s contents for any sign of a flag, looking for a string in the format FLAG1{md5hash} or FL@G1{md5hash}. Sure enough, as soon as I spotted the flag, I grabbed the hash and submitted it (just the raw 32-character hash, no brackets).

Trying robots.txt is always worth it and it often points to other files or directories you might want to explore, and it’s a classic starting line for web-based CTFs. It’s quick, easy, and sometimes the solution is hiding in plain sight.

Flag 2: What website is running on the target, and what is its version?

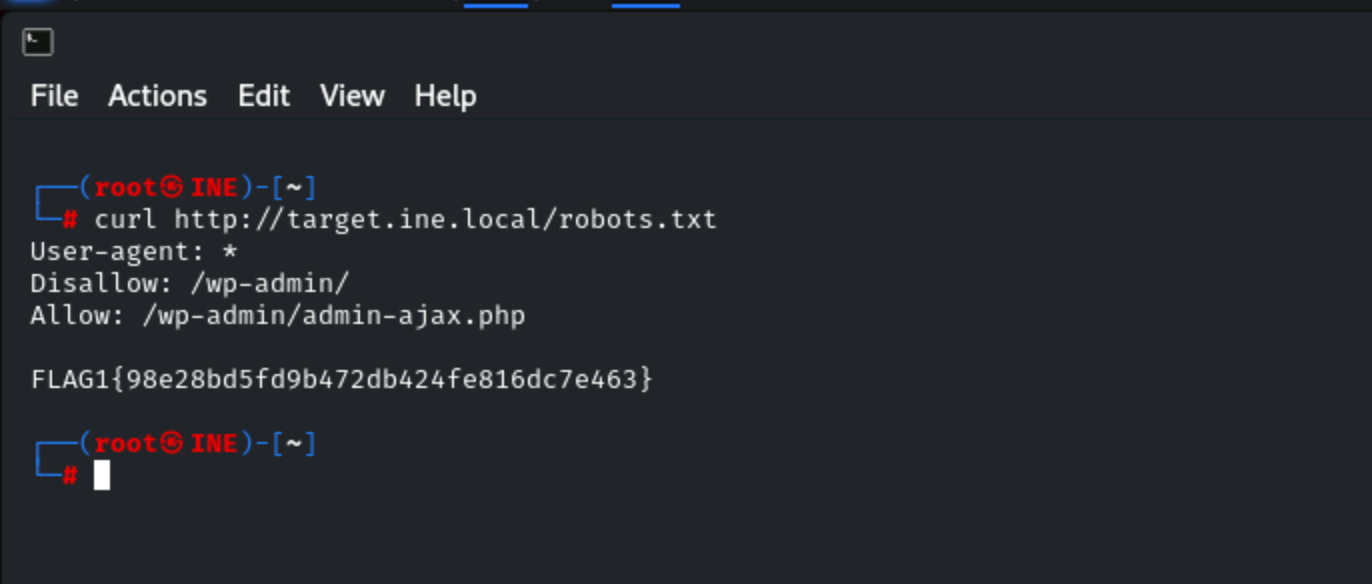

The next step was all about identifying what software the target website was running, and what its version was. Instead of manually checking headers and source code, I reached for a go-to tool: WhatWeb.

I ran:whatweb http://target.ine.local

This tool is super handy for quickly detecting things like web servers, content management systems and their exact versions.

Sure enough, WhatWeb spotted both the web server and CMS:Apache/2.4.41 (Ubuntu)

WordPress 6.5.3

That matched up perfectly with what I was seeing in the HTML and response headers. With the version info in hand, I submitted the value per the challenge rules in the specified flag format.

Using WhatWeb is a huge time saver, it’s basically reconnaissance on autopilot, and it nailed Flag 2 for me within seconds.

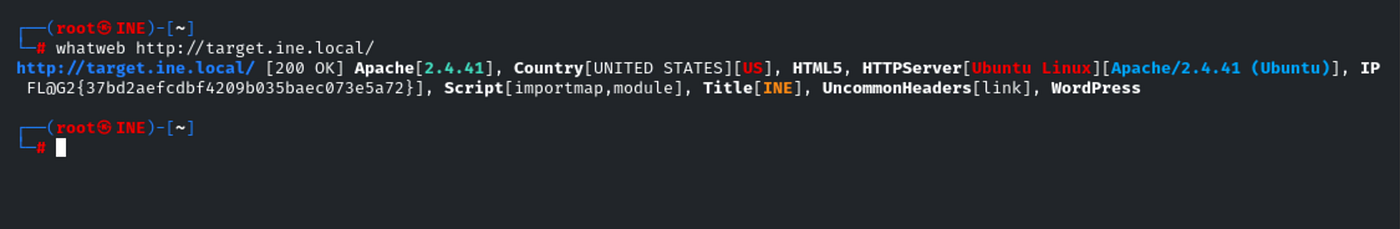

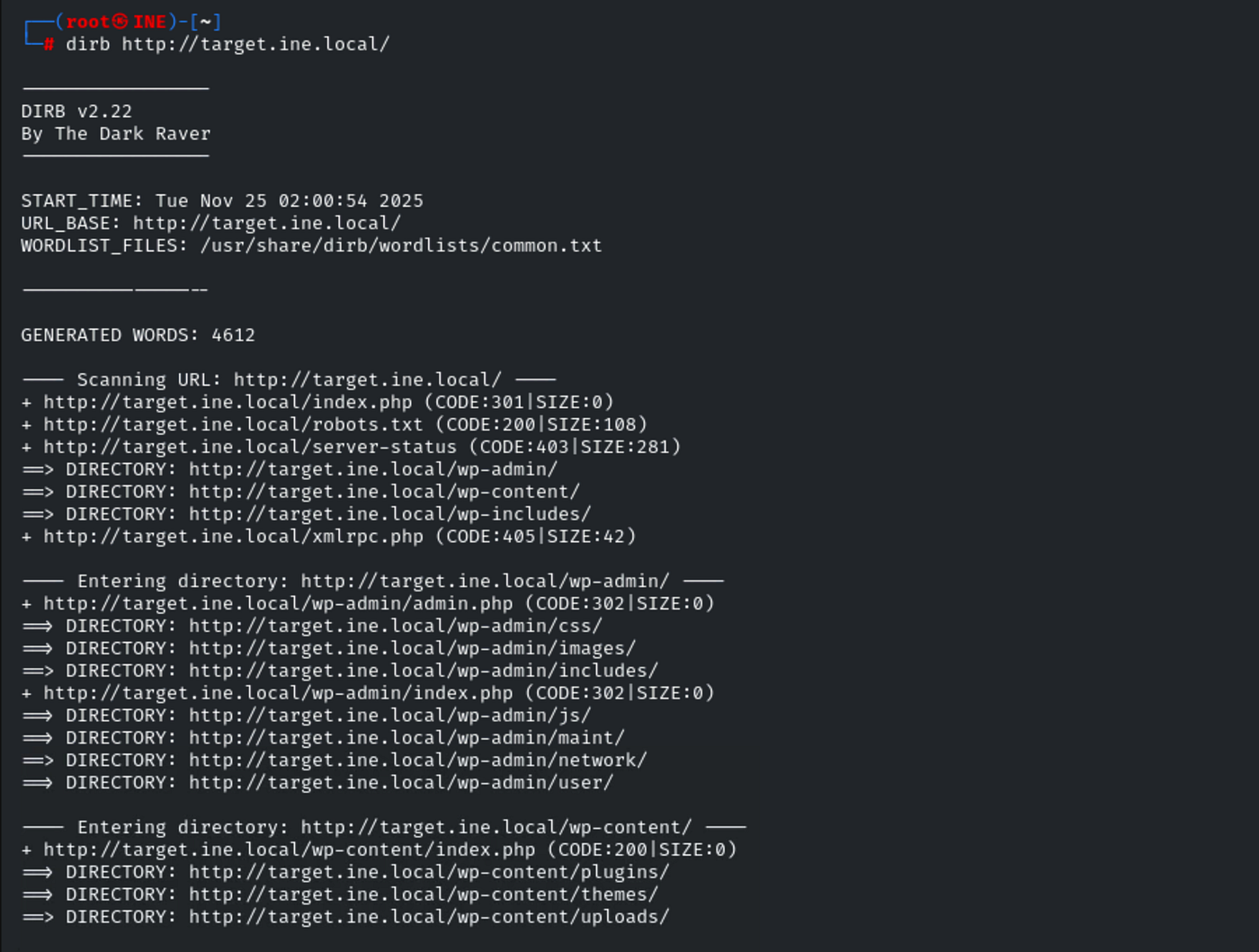

Flag 3: Directory browsing might reveal where files are stored.

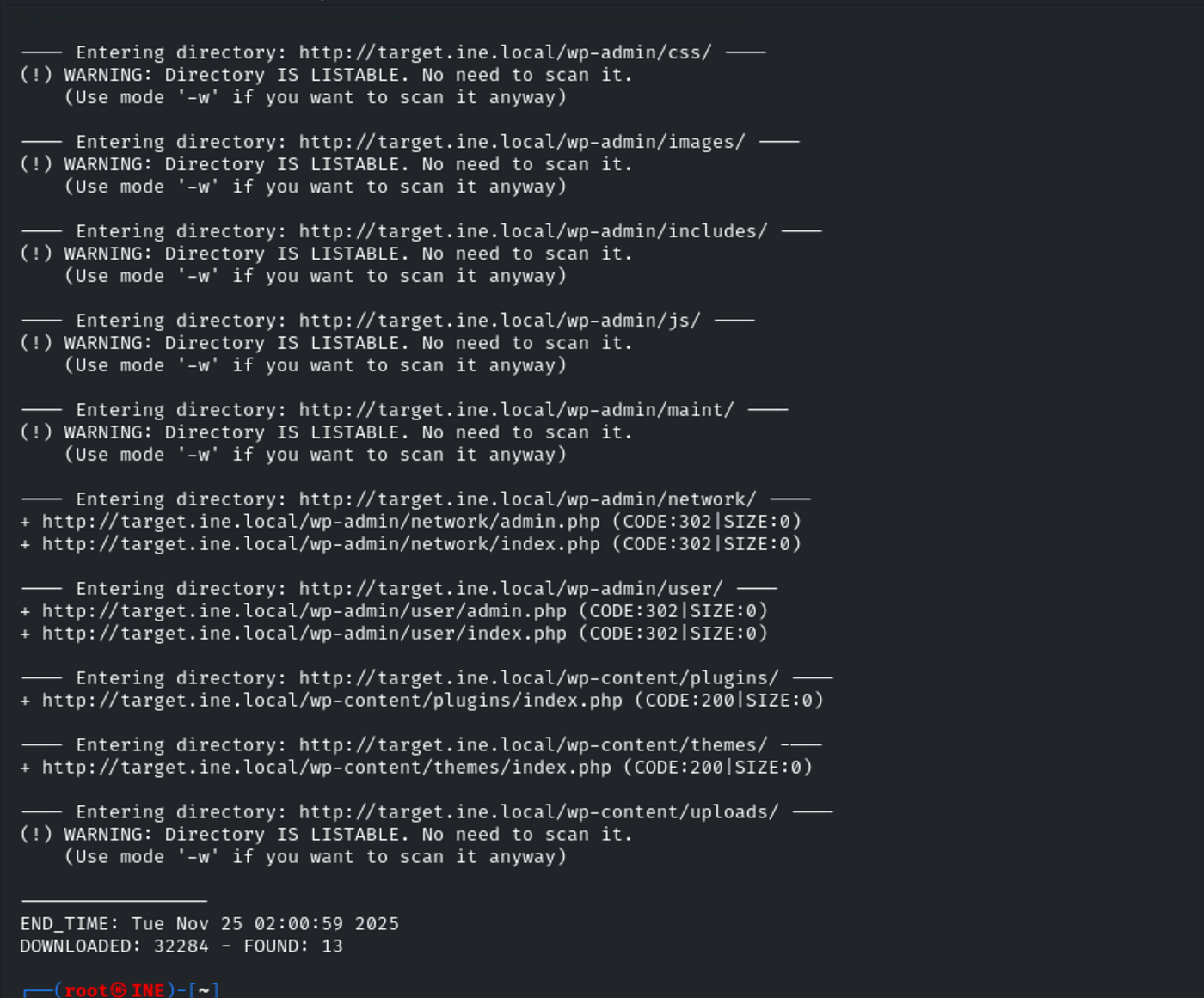

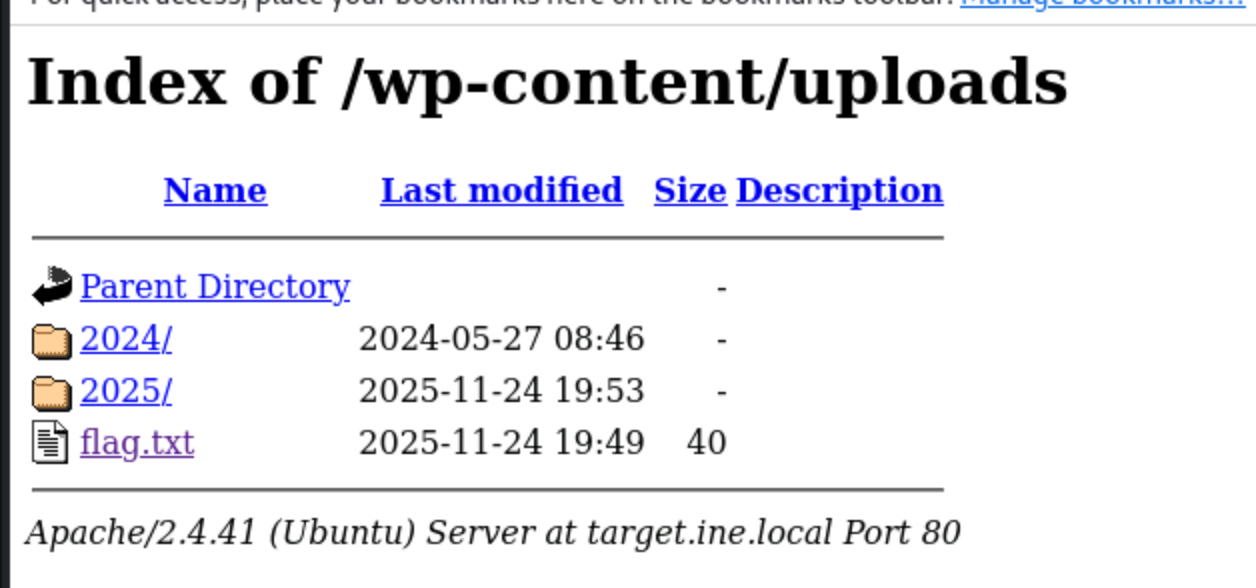

After running dirb and getting a bunch of results, I went through each link one by one, checking if any directory was open or offered up something interesting. It’s a bit tedious but sometimes you just have to put in the work, flags can get tucked away anywhere.

Sure enough, after poking around, I eventually landed in the wp-content/uploads directory. That’s where the flag was sitting, just waiting to be found.

This is a textbook case for why you always sweep through every directory dirb uncovers, especially upload folders. These spots often get less attention from developers and end up exposing files (or flags) that should stay hidden.

By combining dirb’s brute-force scan with a manual review of the results, I tracked down Flag 3 right in the uploads folder like a classic CTF move.

Flag 4: An overlooked backup file in the webroot can be problematic if it reveals sensitive configuration details.

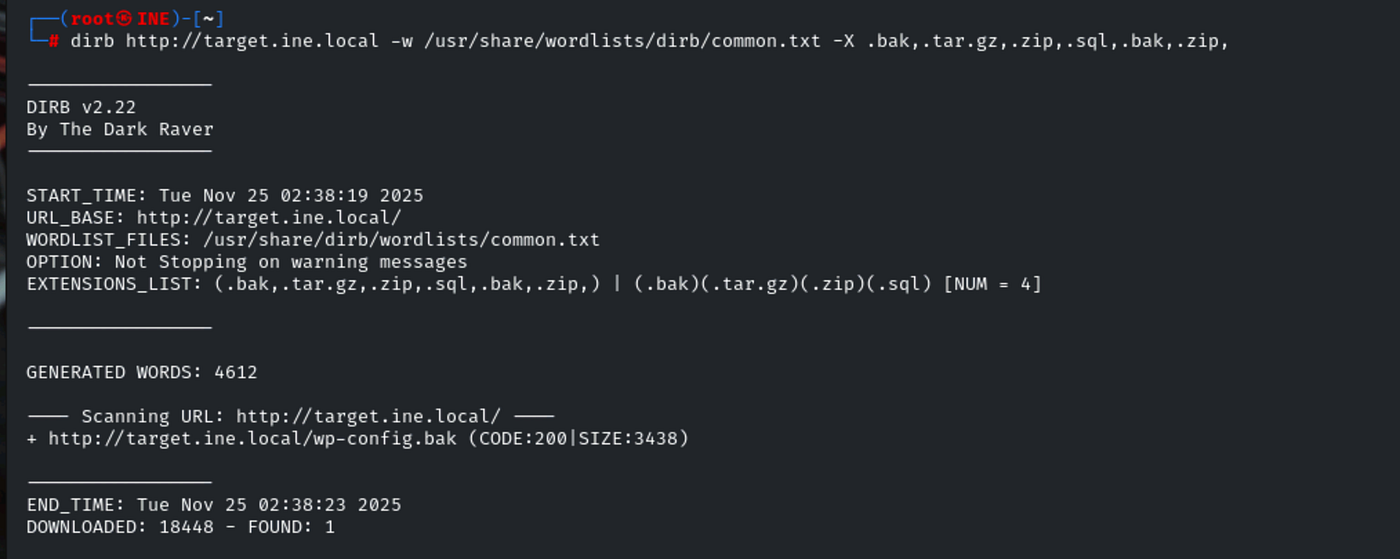

This one’s a really common real-world security issue, and I see it a lot in CTFs. The challenge made it clear: backup files left in a website’s root (webroot) can be a goldmine for attackers if they contain things like configuration details or credentials.

To track down a backup file, I leaned on DirB again, this time customizing the scan. I used a bigger wordlist and told DirB to try lots of classic backup file extensions things like .bak, .tar.gz, .zip, .sql, .bak.zip. Here’s the command:dirb http://target.ine.local -w /usr/share/dirb/wordlists/big.txt -X .bak,.tar.gz,.zip,.sql,.bak.zip

This instructs DirB to append those extensions to every word in the list, making it much more likely to find accidentally exposed backups.

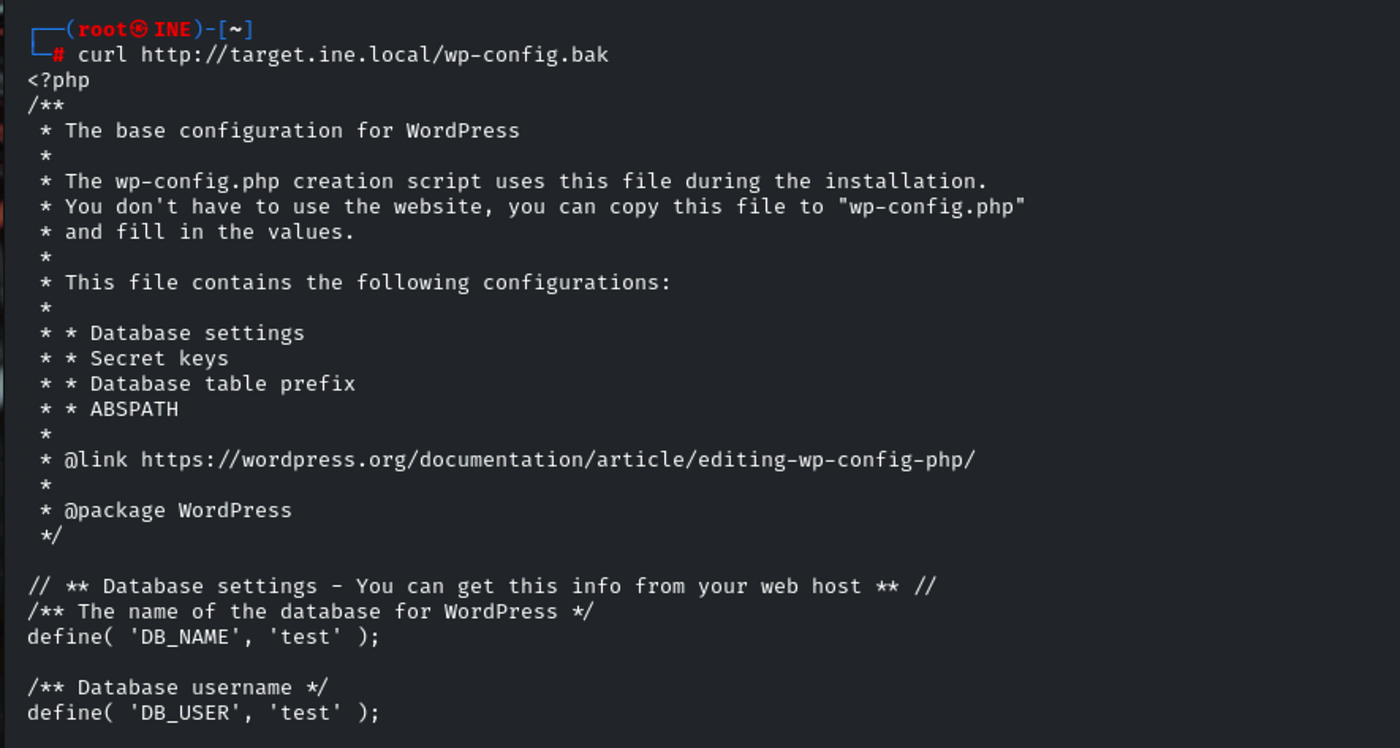

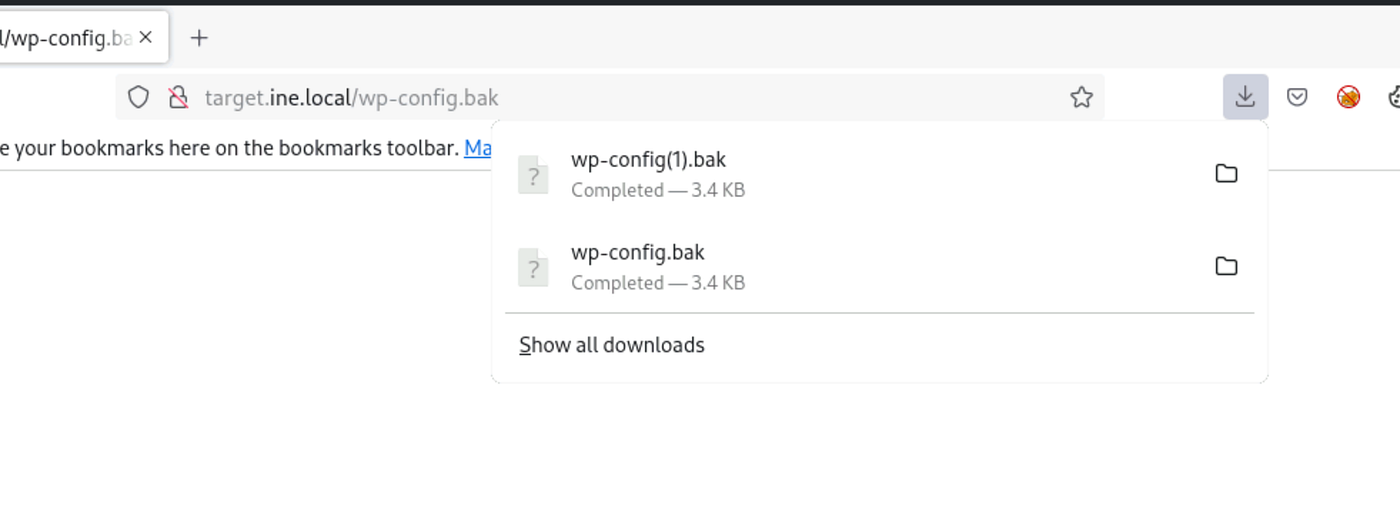

Sure enough, the scan found a file like wp-config.bak in the webroot a textbook example. I downloaded it:curl http://target.ine.local/wp-config.bak

Opening that file, I found database credentials and (most importantly) a flag in the challenge format.

It’s a good reminder: backup files can reveal everything if left out in the open, so they should never be accessible from the web. This challenge shows exactly why penetration testers are always on the lookout for them and why you should be, too.

Flag 5: Certain files may reveal something interesting when mirrored.

The last flag required using HTTrack, a tool for mirroring entire websites for offline analysis. The goal: by downloading the target site, you can uncover files that aren’t easy to find by just browsing or brute-forcing directories while online.

First, I made sure HTTrack was installed:sudo apt install httrack

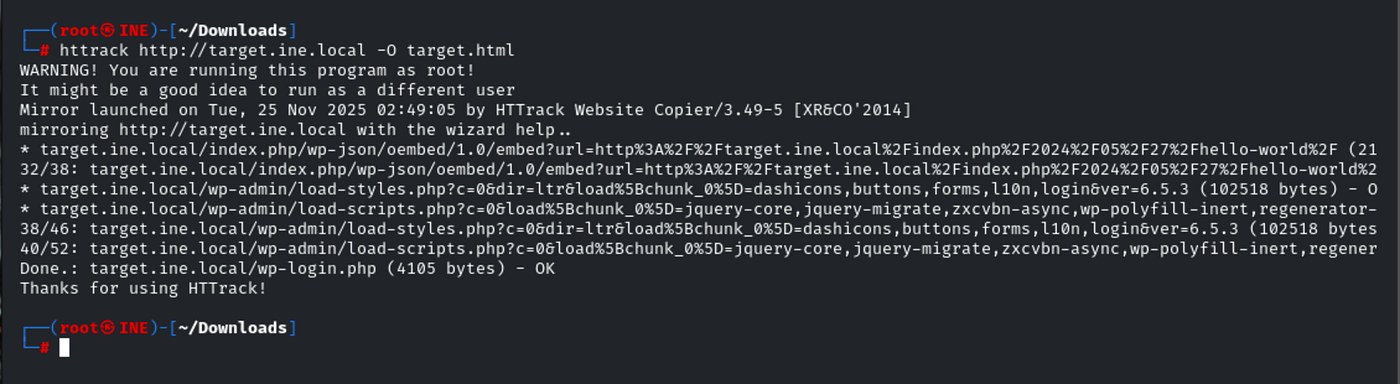

Then I mirrored the site with:httrack http://target.ine.local -O ./target.html

(This command creates a directory named target.html containing the full website structure.)

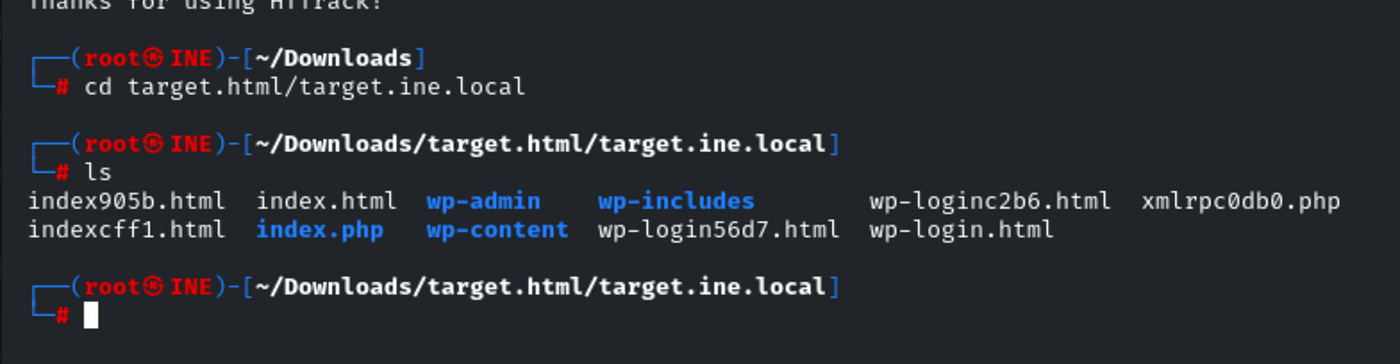

Once the download was complete, I navigated into the mirrored site’s folder:cd target.html/target.ine.local

ls

I manually inspected the files and directories offline, which goes much faster than checking them one-by-one over the network.

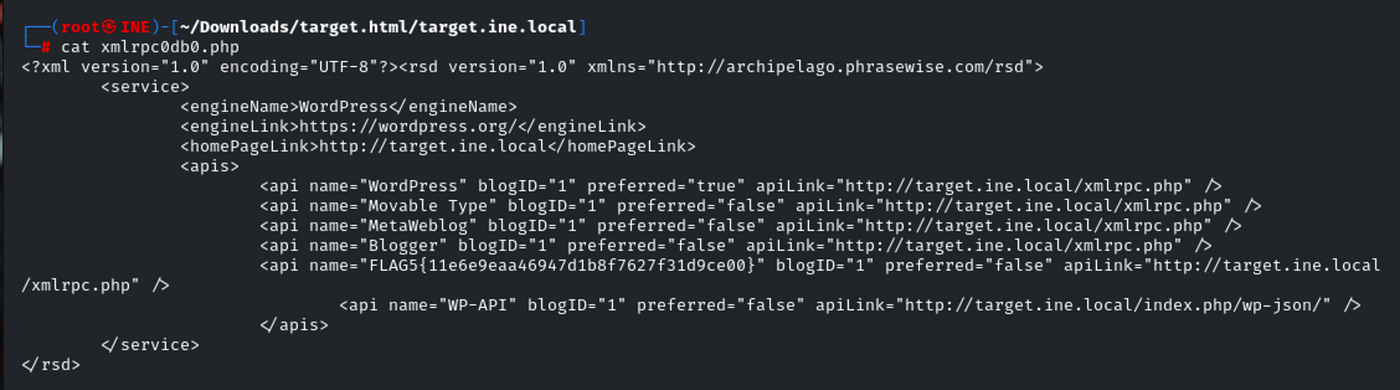

During this exploration, I found a file called xmlrpc0db0.php. Using:cat xmlrpc0db0.php

I discovered the flag hiding inside:

This challenge is a great example of why mirroring tools matter in web CTFs and real-world app assessments, sometimes important files are present but completely unlisted online, making them invisible unless you grab the whole site.

So, by installing HTTrack, mirroring the site, and systematically digging through the mirrored content, Flag 5 was found and submitted successfully.

Wrapping up this Skill Check Labs CTF, I got to put a range of classic web hacking techniques to the test from analyzing headers and fingerprinting versions to brute-forcing directories and mirroring full sites for hidden files. Each flag reinforced a different approach, showing why it’s important not just to focus on the obvious, but to dig deeper for those easy-to-miss vulnerabilities.

Tools like curl, dirb, WhatWeb and HTTrack don’t just speed up these kinds of challenges they’re invaluable in real web security work. Even with straightforward clues, carefully reviewing every output and checking every corner pays off.

Overall, this lab was a great exercise in hands-on reconnaissance and gave me a solid refresher on the value of persistence, curiosity, and having the right tools for the job. Looking forward to tackling the next set of challenges, applying what I learned here and hunting down more flags!

No comments:

Post a Comment